|

Rating:

Author: Patti Hill

Co-author(s): Patti Hill Publisher: Garden Wall Press Published: 2016-04-25 ISBN(s) 978-0-692-65923-6 Language(s): English Category: Fiction Audience: Adult Genre(s): Contemporary, Romance, Women's Fiction Read Excerpt > 1

I’m no Cinderella. Enchanted pumpkins and singing mice have nothing to do with my story. The regulars who came to the telephony to chat with people from their pasts—some I suspected to be quite dead—simply provided a rhythm to my day, but nothing much changed. I woke each morning to the nagging whine of Brian’s alarm clock, an uncomfortable reminder that my life had forever changed and would forever be the same, magic or no. Think about it, real people don’t actually live in enchanted woods, where the only jobs are evil step-mother and handsome prince. In the real world of bills-must-be-paid, I managed my family’s bait shop and telephony (read that: telephone museum) across the street from the San Clemente pier. My own encounters with magic were purely secondhand in the beginning. The first tick of the clock found me refreshing the newsstand with current editions. Next door at Canatello’s Ristorante delivery trucks dropped off produce and wine. At 5:20 a.m., Eric dollied frozen bait through the door and begged a cup of espresso for the drive back to the harbor. If he arrived fresh-shaven and lingered, glancing toward the back of the bait shop to my bedroom, he stayed longer and the shop opened late, a simple hiccup of time easily recovered. Tick! On those mornings of disappointing delight, the fishermen huddled on the sidewalk past our usual opening time. They bypassed the espresso—too fussy—for drip coffee, which was strong and burned by the time I unlocked the door. If customers must be faced early in the morning, fishermen were the easiest to please. As a group they defined their suffering more sparingly than others. Herb, a Vietnam vet with a salt-and-pepper braid, bee-lined to the counter. “Hey there, Jenna, you got any of that sludge you call coffee?” Like I said, easy. We generated absolutely nothing toward the bottom line from the adjoining telephony—a creation of my father’s. Regulars visited the telephony daily. First came Ginny, a woman with tangerine spikes of hair and an electric alertness, just before nine to wait by Model 302, the first Western Electric telephone to include the ringer and network circuitry in the same desktop unit. Ginny’s appearance cued me to chill the soft-serve mix to be ready for the beach crowd. Tick! In the beginning, the bait shop had been larger. Instead of old telephones, the connecting space housed the Pierside Rental Shop. Every kid coming from the Inland Empire needed a surf rider to experience a better-than-average day at San Clemente beach. And we’d actually made money renting the things to the little boogers. But Dad had needed a place—and a reason—for all the telephones he’d collected in the years since Brian’s disappearance. The doorway between the two storefronts had been narrowed to increase wall space for day-at-the-beach essentials on the bait shop side and countless telephones on the telephony side, which made keeping an eye on the regulars difficult, not because I didn’t trust Ginny. She could take as many telephones home as she could carry in her knitting bag and I wouldn’t care, but she would never do such a thing. The truth? I liked to watch and listen. While she waited for the 302 to ring, she knitted caps for orphans somewhere in Central America, a place where people wore snake boots to walk through the forest. Costa Rica? It might have been Nicaragua. Anyway, I couldn’t actually hear the telephone ring for Ginny, but I could hear her talking, although not her words. Her voice fluttered like a bird caught in a trap. Most days I delivered a cup of tea to Ginny, my way of snooping without being obvious. I usually found her leaning over the small desk, perched on the chair with butt-biting springs and her knitting discarded in a heap. She acknowledged the tea with a pat on my hand but kept talking. “I hear you, Frank. You don’t have to yell … No one’s listening. I can tell when Debbie gets on the extension … It’s been so long. I can’t bear not knowing another minute. When will you forgive me?” If the 302 didn’t ring for Ginny by nine-fifteen, her knitting needles clicked a distress signal, much more discomforting than her pleadings with Frank. And so, I delivered an extra-large cup of tea with cream and sugar, the Valium of the British and cap knitters everywhere. At the end of her time in the telephony, around ten-fifteen, she insisted on paying for the tea she didn’t order. I refused her money, but each Christmas she knitted me something—at least a dozen caps over the years, plus a family of mice and some socks meant to look like watermelons, which I wore to bed all year long. Soon after Ginny slipped out, Mr. Foster shuffled in, leaning hard on his walker. He arrived at ten-thirty. To my knowledge, the Kellogg ashtray telephone had only rung three or four times for Mr. Foster. There was no need to serve him tea to hear what he said. He yelled loud enough to drown out the sinners in Dante’s third ring of hell. “You have got to believe me! I’ve never lied to you. And I won’t start now!” When my stomach gurgled around noon, I knew Tim would soon arrive. Tick! He was a buttoned-up accountant with round blue-gray eyes and a face that was boyish but serious. He moved like an athlete, although I doubted he stood a full inch taller than me, and no one had ever accused me of being tall. More than once I’d thought of reaching out and undoing the top button of his shirt. He looked positively choked, especially in the heat of summer. Unreasonably pleasant and earnest, Tim probably recited the Boy Scout pledge in the mirror before leaving for work. Tim brought two containers of leftovers to heat in the microwave each visit—one for him and one for me. He liked to experiment after watching cooking shows. Mostly, his experiments resulted in restaurant-quality food. His culinary skills made him my favorite. The Snoopy telephone rang for him during his lunch hour, Monday through Friday, again without my hearing. He talked to his younger sister Amy. Brian had been gone for seventeen years, but the way Tim talked to Amy made me miss my brother all the more, even though Brian had never shown me much concern. Memories are odd that way. I displayed the Snoopy telephone on a nightstand in the front window. Tim never flinched at the attention he drew from passersby, although some considered a grown man talking on a Snoopy telephone hilarious enough to point and laugh. I didn’t move the telephone, which I probably should have, but the placement of Snoopy kept Tim in my line of sight and only ten feet from the cash register. I heard every word from his end. “You shouldn’t worry about them,” he said. “Guys can be cruel. They say stupid stuff they don’t mean, not just to you, to everyone. You’re beautiful … Brothers know these things. I have a reputation to uphold … I would hide you in the attic if you were that ugly.” On his way out of the telephony at twelve forty-five, Tim collected the washed containers from the previous day and thanked me for letting him come. In the typical gloom of June, when fog clung to the coast and customers were sparse, he sometimes broke off his conversation with Amy early. He leaned against the counter to ask about my day or to tell me about his most recent orienteering event. He recounted every obstacle in painstaking detail—the views he enjoyed at the pinnacle of an ascent and the advantage some opponents gained by not following the rules in spirit, whatever that meant. When the day came for Tim to finally win, I hoped he won big. More than once I’d been tempted to ask if he had a younger brother, one as good at the stove but more dangerous, less predictable, taller. I didn’t have the heart. In between customers, I spent the afternoon doing the perfunctory jobs around the shop and telephony, which included restocking merchandise and placing orders, plus ridding the glass cases of fingerprints and the telephony of dust. And paying bills when I had the money. At three p.m., Dad arrived breathless from dashing to the store from his workshop, where he refinished and repaired telephones to sell on eBay and at telephone-lover conventions. Sad but true, he wasn’t the only telephone-crazed person on the planet. Tick! He knew not to be late. While he played barista and clawed through the freezer to find squid or mackerel for a fisherman, I ran errands for myself and Mom. I raced to be back before my last regular of the day arrived. She liked to slip in as the Metrolink passengers selected snacks for the 5:02 inland, the busiest time of our day. I’d not managed to learn the woman’s name, but she sat in front of the Whitman & Couch fiddleback, an odd telephone choice for a woman in her twenties. She spoke too softly for a word to be heard. And I rarely saw her leave. She dissolved into the ebb of the late-day crowd. I didn’t mind that the telephones in the telephony didn’t ring for me. Dad had warned me about involving myself with those on the other end of the line. Such carelessness, he assured me, only led to heartache. I’d heard for myself the frustration of the people on this end of the line and decided not to get involved. I locked the door at five-thirty and headed upstairs to eat dinner with my parents. Thirty-four, single, and sleeping in the backroom of a bait shop. If my very own fairy godmother showed up, she would cinch closed her bag of magic dust and fly off to find a more hopeful recipient of her goodwill. Tick. Tock.

2

I found the boxes of hair dye under the passenger seat. They’d been in my car for at least two weeks. Clairol had yet again discontinued Mom’s hair color. Why the company felt compelled to take a perfectly good hair color and toss the formula to the wind, I would never know. I’d traipsed to every drugstore in south Orange County. I’d even slipped a clerk a five at a store in San Juan Capistrano to search her storeroom for returns. No such luck. Now I stood outside the apartment, constructing lies and excuses for being late to color Mom’s hair. For good reasons Mom held little faith in my chemistry skills. I’d convinced her to mix colors before with disappointing results. I stuffed the boxes inside my purse and opened the door. She stood studying the view, a tiny paintbrush poised in her hand before an easel. The breeze rattled the vertical blinds and lifted her bangs. I expelled a long-held breath. She squinted down on the vista, painting the landscape on the inside lid of a cigar box. Her scrutiny reassured me, ever so slightly, that the play of light and shadow, line and form still roused her to life. This was the mother I remembered from childhood and into my teens. Mom dabbed at the clouds in her painting and stepped back, tilting her head. “Finished?” I stepped behind her. The scene was familiar, the one scene my mother painted, the San Clemente pier. Only the participants changed. In this painting a group of surfers huddled to pass a joint, a mother pushed a double stroller—she should not have been wearing a bikini—and an old man bent over to offer his attentive Yorkie a treat. He should have been wearing a belt. I looked out the window to see the echo of her painting. She’d caught the blushing gold of the fading day and the long arm of the pier reaching toward the horizon. “Your best ever. The sky is perfect. I’ll take the box down to the shop when it dries. This one will sell within the week.” She ran a hand through her short hair. “My hair feels like straw. You promised me a haircut ages ago.” I pulled the first lie from my hat. “I like your hair a little longer. It’s cute.” “Brian won’t recognize me. And my color. Jenna, let’s cover this gray before dinner. I would hate for him to come home and see me like this.” Rather than allowing her desperation to gutter me, I studied the shimmer of light off the water, selecting my next combination of lies carefully. “I need to do an inventory in the shop and make a run to Walmart. We’re getting low on sunscreen and diapers. And I’m thinking about picking up a case of baby formula. A frantic mother came in last week. We’re missing a market there.” Mom narrowed her gaze. “Since when are you in a sweat to shop Walmart?” Dig deeper. “I think you should consider letting your hair go gray. We could get some gel, spike it. Nothing could be easier.” I lowered my voice. “And don’t forget the chemicals in the dye. No one knows how they pollute our bodies over the long term.” Mom’s eyes welled with tears. “You know how important this is to me.” I knew too well how irrationally non-negotiable she’d become about keeping herself and the apartment as Brian had last seen both. Keeping the aging appliances running, the hinges from rusting off the cupboards, and the carpet from becoming a tripping hazard fell to me. Rather than scream over the hair dye, I introduced unvisited logic. “Brian will be different too. He’s older. He’s probably thinning on top and has grown a beard to compensate. Knowing Brian, and you know this to be true, he’s shaved his head to spit in the eye of balding.” Never in the seventeen years Brian had been gone had anyone in my family suggested he could be anything but exploring the world, certainly not that he could be anything but alive and well. Not to Mom. Not out loud. “I’m betting he has a potbelly, like Dad.” She slumped into her recliner and worried the exposed piping like a rosary. “Everything has to be the same.” No problem there. Nothing had changed. True, the furniture had frayed and sagged with age, but the push-button telephone still hung on the kitchen wall; and the family photographs scattered about the apartment all predated the year Brian had disappeared. I certainly wasn’t the same. I was young enough but no longer fresh. If Mom looked closely, she would see gray hair at my temples. I wouldn’t color my hair for Brian or anyone else. The clerk at the drugstore had leaned in close to suggest an eye cream, but I’d opted for bug-eyed sunglasses. I draped my arm around Mom’s shoulders. She was all rafters and beams under my touch. “They’ve discontinued your color.” Mom stifled a sob. I continued quickly, hoping to staunch a full-blown cry fest. “I bought two boxes, one shade a little darker and another bottle a shade lighter. The mixture should be perfect, really. The clerk helped me.” I omitted that the clerk looked twelve and dyed pink streaks through her hair. Mom ran to her bedroom and sprawled across the bed. I followed, knowing I’d emptied my pockets of logic and lies, and all the stale platitudes I’d whispered into her ear over the years. I certainly didn’t believe them, and I feared she no longer believed them either. I crawled onto the bed and rested my hand on her heaving back. I squelched the urge to mouth her muffled words. I lay there, instead, as helpful as a mustard plaster. Mom’s bedside clock clicked with each passing minute. Outside, the Metrolink crossing clanged, and the train’s horn bellowed. Her breathing slowed. “I can still smell his milk breath, feel his puffs of breath on my face. The heat of him against my chest. He packed a fire even as a baby. I remember everything about Brian.” “I know.” “Brian,” she whispered, and her tears redoubled. A bar of sunlight rose toward the ceiling. The front door opened. Dad said Mom’s name—no need to shout in a one-bedroom apartment. I answered, “We’re in here.” “I’ll be back late. Thought you should know.” The door clicked shut. “Are you hungry, Mom?” I said to distract her from Dad’s sidestepping of her pain. But if she’d heard him—how could she not?—she didn’t react. She rolled onto her back. “I woke up every morning to find Brian sleeping on your father’s chest. He adored him.” “Brian was special,” I said, remembering a much different brother than she described. I would now hear how he’d never cried or whined or thrown temper tantrums. In her mind, Brian was sunshine to my dark side of the moon. He shone like a fresh summer day. I was the storm arriving like clockwork over the prairie with billowing clouds and strikes of lightning. “Do you think the dollar store might have my color?” she said, her voice clogged with phlegm. “Been there. Actually, I’ve been looking for weeks, everywhere. We either try combining the two colors I found, or you’ll need to go see Suzanne.” Mom blanched. “You know what that woman does to me.” I’d just committed emotional terrorism on my very own mother. There wasn’t a boundary Suzanne wouldn’t climb over, cut through, or plow down. “As long as the clerk helped you,” Mom said, reaching for a Kleenex to blow her nose. The clerk had told me which aisle to search. “Of course she did.” “Well then, I have no choice but to trust you.” I wasn’t a praying woman, but I did wish for a happy collision of Coastal Sand and Sunflower as I mixed and shook the applicator bottle. When we finished, Mom stood in front of the mirror, freshly coifed and hair-sprayed. She arrived at the dinner table wearing mascara and lip gloss. She looked better than I’d seen her in over a year. Mom went to bed early that night. As far as I knew, Dad never came home. I worked at making cover-ups from faded San Clemente T-shirts and flounces of old curtains at the dining table. Selling the cover-ups gave me some pocket money. Women will buy anything to cover-up cellulite. When Jimmy Fallon finished his monologue, I headed for the bait shop and bed. Yet another wondrous night in paradise.

3

Playing hairdresser to Mom revived dreams of stuffing my rubble into a Trader Joe’s bag and driving as far as my pitiful 1990 Daewoo Le Mans would take me. Hesperia? Barstow? Probably Tustin. Not far enough. Besides, who would buy Mom her paints, fill her cupboards with groceries, and hunt every store in south Orange County for a discontinued hair dye? And who would work for practically nothing to keep a failing business afloat? Dad? Not likely. Even less likely now that he was the one packing his suitcases and piling his miscellany into beer boxes. I sat on the edge of his chair and watched as he selected books from the shelf. By habit I sat out of striking distance and poised myself to flee, keeping one eye on the veins in his temples. I hadn’t been this wary since high school but neither had I been this angry. I worked to keep my tone inquisitive rather than accusatory. But I was feeling reckless. “You’re leaving her? Now? How will she…do anything?” Dad threw a few books in a box and turned toward the dresser that served as a TV stand in the living room. He lifted a handful of black socks and dropped them into his suitcase. “How long has it been, sixteen—?” “Seventeen,” I corrected. “What?” he asked, surprised, stopping to look at me, frowning as he counted back the years. “Seventeen years, Dad. Brian has been gone for seventeen very long years—a lifetime, half of mine.” Dad glanced toward the bedroom. “Your mother hasn’t adapted well.” A slap would have hurt less. This proved Dad hadn’t a clue about what his leaving meant to us. He might not have been the most pleasant person to have around, but he was a person who knew how to dispense drugs and be somewhat present. My hurt morphed back to anger. “How, exactly, do you adapt to your son disappearing?” “We do what we have to do,” he said, matching my anger with condescension. Geesh, he was bumptious (new word: self-assertive or proud to an irritating degree). He drew in a breath. I prepared for an outburst of indignation and a generous spray of spittle. Instead, he released a slow, even breath. “Listen, Jenna, we both know your brother was a lost cause by the time he left. We gave finding him our best shot, but he’s out there—and you know this is true—he’s out there, somewhere, having a heck of a good time, leaving us to handle your mother like a basket of eggs. Well, I’m done.” I did not know anything about Brian. In fact, I’d spent most nights between wakefulness and sleep, picturing Brian in every possible situation, most of them horrific—a prison in Turkey, a diamond mine in Angola, forced to fight in the Congo. “Brian will be found when Brian is found,” Dad said, putting a period on the conversation. Not so fast. “Who’s looking? Are you?” Dad opened the second drawer to retrieve plaid boxers. “Brian has moved on. We need to move on too. If he saw us holed up like this, he’d have a good, hard laugh on us. There’s no denying what’s true.” “Can you wait until Mom calms down to talk about this?” Dad gestured toward the closed bedroom door and dropped his arm. With a crooked grin, he said, “She’s gleeful over the extra closet space. She now has plenty of room for everything she buys on QVC. See, everyone’s happy.” Dad lifted a stack of undershirts from the bottom drawer. He zipped his suitcase closed and opened his wallet to fish out a business card. “You can reach me here, at the home number. And I’ll come by to relieve you in the afternoon, as usual.” The business card belonged to a Realtor, a blonde, cute in a Botoxed sort of way. Sally McCallister. For all of my life, Dad had referred to Realtors as glad-handers and bottom-feeders, swimming down there with lawyers. And now he was living with one. He hefted the suitcase to the floor. I looked around the apartment, all but the bedroom and bathroom visible from where we stood. Nothing of my father remained, not his crossword puzzle books, not his collection of antique telephone catalogs, not even the rug Mom kept in front of his chair. “Sally’s a real nice gal, likes to travel and go out to dinner,” he said. My heart thumped. He was really leaving. I spoke through clenched teeth. “You’re abandoning Mom!” And me, Dad. You’re abandoning me. “Jenna, your mom and I haven’t had a real marriage in a long time. You’re old enough to understand.” I cast caution to the seagulls and pulled Dad onto the balcony. The sliding glass door closed with a thud. Below us, beachgoers walked languidly. He needed to understand certain things too. “I’m leaving. I’ve been accepted in Rochester—” “New York? That Rochester? Or Minnesota? It’s cold in Minnesota.” “New York, Dad. I’ve been accepted into their sonographers program. I’ve waited—” “And how will you pay for this?” Leave it to Dad to deflect the real issue. I pivoted away, stopped and turned back. He could fear my spittle for a change. “I plan on doing what I always do, work my butt off.” I repelled from his touch. “You should go,” he said. “We can hire someone to work the shop. Selling beach garb isn’t exactly rocket science.” “And Mom?” “She’ll be fine.” There had been a time when I’d believed this too. Mom needed to get out of the apartment, and the motivation would magically appear with us refusing to meet her every whim, calling her bluff, letting her get a little hungry. I didn’t believe in magic anymore, not that kind. Mom had changed. She’d slipped into a darkening place. She gave the same excuses for not leaving the apartment, but her eyes no longer reflected light. What had started as a vigil had become a prison. The world, even the world of sand and surf across the street, a paradise to most, threatened her. “I don’t think so, Dad. She’s changed.” He shrugged. “We can’t help someone who won’t help themselves.” “But we could try being decent. You know, sticking by her in her time of need?” He pushed past me and re-entered the apartment. He spoke over his shoulder as he stacked boxes. “Do whatever you want.” “That’s not an option, thanks to you. You’re leaving me here to rot.” Dad’s voice turned velvety. “Only if rotting is what works for you.” Where did that come from? I studied the Realtor’s card. A woman in a navy blazer smiled back with teeth the size of movie screens. I held the card in front of his face. “That sounds like something Sally here might have heard at a real estate agent’s convention.” He stepped toward me and I backed into his chair. But Dad wasn’t angry. He looked like he’d dropped his ice cream on a hot sidewalk. “You’re not being fair.” “Just following your lead, Dad. Does Mom know about Sally?” How could she not? He balanced a stack of boxes on one arm and opened the door. At sixty-three, I still marveled at his strength. “I’ll see you at three.” He turned to quickstep down the stairs to the sidewalk and his waiting car. If he drove away from me now, I would be stuck with the telephony forever, which would keep me living with Mom. I swallowed hard and followed. I stepped between him and the car door. “This is ridiculous,” he said and dropped the boxes to the street. A pair of surfers stood at the counter in the bait shop, shifting from one foot to the other. They could wait for their board wax. I turned back to Dad who stared at the horizon, a convenient delaying tactic for all of us who lived on the coast. I put my hand on his arm. He startled, but he looked at me. “Dad, there are other things we need to talk about. Profits are close to nil. We should move the telephony to make room for something that makes money.” “I’m not comfortable moving the telephony. Who knows what might happen?” “What could happen? You move the telephones from one place to another, and the retail space starts bringing in income.” “And our regulars?” Dad knew the regulars were my pets, the rhythm of my day. My whole world. I would miss them. On the other hand, I didn’t see the telephony making them happy. “We might be doing them a huge favor. You could sell the telephones on eBay and take Sally someplace nice.” Dad shot me a warning glance. “I need time to think.” This was Dad-speak for: the telephony will stay put. I gambled on upping the stakes. “Maybe Mom could move in with you and Sally.” “End of conversation. I’ll see you at three.” He threw the boxes into the back seat and zoomed up the hill and disappeared around a cliff of apartments. Something in me snapped and slackened.

i found mom laying her clothes out on the bed by color and type of animal print with a heap of newer things on the floor. She gestured to the pile dismissively. “Brian’s never seen me in those. Take them to Goodwill on your next trip.” What did people say at the end of a marriage? “I’m sorry, Mom.” She stopped, frowned. “Sorry?” “Dad leaving.” Me staying. “For heaven’s sake, he was never here. And look at the closet space. There are things in this closet I’d forgotten about, but Brian will remember.” She pulled out a periwinkle golf shirt. “I wore this to his fifteenth birthday party. I’m finding treasure, Jenna.” My knees softened. Mom hadn’t demonstrated this kind of exuberance since before Brian hit puberty. How could I have missed her ambivalence over Dad? Maybe I hadn’t. Maybe I’d ignored her detachment, or was I too busy trying to keep her keel in the water? Whatever my culpability, the changes in her felt like a millstone. “We’re down to me and you,” I said. “Maybe you could try going out, not far. A trip to the post office would be nice. We’ll be back in ten minutes.” The color slid from Mom’s face. “And if Brian comes home?” “We’ll leave a note. And we won’t lock the door.” She dropped the golf shirt to the floor. Her hands fluttered over her heart. “He’ll think we’ve forgotten him.” Forgotten him? Forgotten I was parked in the brush behind the high school, losing my virginity, when I should have been riding the bus home with my younger brother? Forgotten that we hadn’t seen Brian since? That I had to learn to fall asleep without the sound of his breathing in the room, or that my heart had been stuck in neutral for seventeen years, where I feared it was forever lodged, that his absence served as the great black hole that pulled every particle of joy from my life? Forgetting Brian wasn’t possible, not for a minute. I pulled her into my arms. “I’ll find him, Mom. I will find Brian, and I’ll bring him back to you.” |

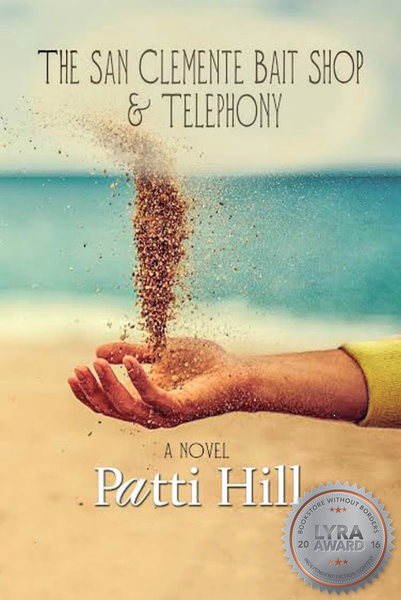

The San Clemente Bait Shop and Telephony

|

See Bio >

Everyday magic transforms ordinary lives.

Something wondrous happens each day in the telephony where Jenna Archer is the de facto curator. Regular visitors receive calls from their pasts with hopes of regaining their futures. Despite these brushes with the mystical, Jenna’s life is less than magical. Her brother Brian went missing seventeen years ago, and her mother’s vigil is more prison than sanctuary. And then a telephone rings for Jenna. She speaks to the last person to see her brother. She must find the man with the menacing voice in the present to discover what he knows about Brian’s disappearance or risk being shackled to her past forever. Love hangs in the balance.

BWB never takes commissions - Authors! Sign Up Now! Only $9.99

More books by |